|

Bowed Neck |

||

|

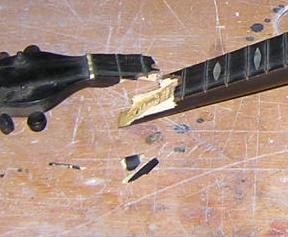

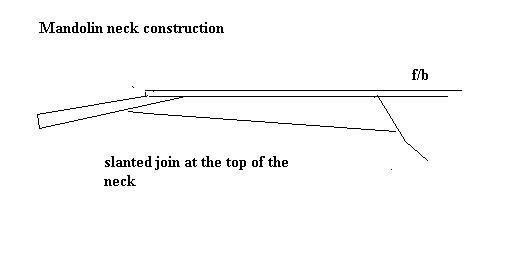

One of the first things obvious in many old mandolins, is that the neck appears warped. This is possible, but the problem is usually movement at the neck-body join. Unseasoned wood, excessive string pressure, or even exposure to high temperatures, can result in movement at the join, often resulting in the neck being pulled up, and/or the back being deformed or split, and sometimes the heel split. If this is more than slight, it will make the instrument unplayable. Technically the neck is not bent, it has moved. |

|

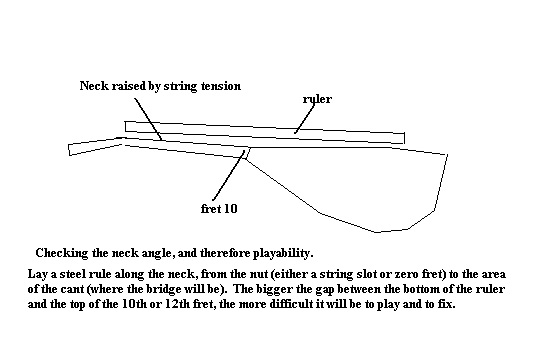

The most fundamental aspect, other than obvious damage which needs to be repaired, is to assess how playable the mandolin is going to be. Re-setting the neck is a difficult and time consuming exercise, and should not be undertaken lightly. All other possibilities should be explored first. Neck movement like this seems much prevalent in Italian instruments than German, and more in bowl backs than other styles. |